Creating the World in His Image

The fact is, that all language about everything is analogical; we think in a series of metaphors, We can explain nothing in terms of itself, but only in terms of other things.

(had some musings over this past year around the idea of worldbuilding and its relationship to idolatry (in the way it creates an image). It's been so long I'm not sure what image I'm even trying to depict here.. but as it's already Christmas it's fitting, as I both wait and remember the coming of the image of God)

This past summer, I attended a panel on worldbuilding. Panelists praised builders like Bernard Arnault, who became the richest man by selling a lifestyle of luxury and status, and Walt Disney, a pioneer in bringing animated worlds to life.

As discussions about Arnault were ongoing, my thoughts drifted towards the essence of worldbuilding: it's clear it's not simply about making a physical product (Louis Vuitton) or location (Disney World), but creating a framing.

Maybe since the focus of the panel in related worldbuilding to business, it left me feeling rather skeptical, leading me to view worldbuilding as a subtle form of idolatry, where builders fabricate alternative realities for people to inhabit and consumers to buy into.

Consider Soylent: it's not just a meal replacement product, but represents the ethos of efficiency, the ultimate answer to hunger. The product embodies an ideal, just another step in the evolution of an outsourced approach to food from self grown produce and grocery stores to meal prep, frozen foods to take-out/drive-through. Efficiency as a value is embodied in a product that overrides the cultural and social experience of cooking for friends/family. If it's not happened already, I could easily imagine a future upgrade becoming more reduced: a pill or even an IV.

This reflects a broader societal obsession of optimizing only what is measurable. While diligence and measurement are useful, over emphasizing utility leads to absurdities, like Google A/B testing colors of buttons at (who cares about taste when you can measure effectiveness). At the individual level it leads to hoarding credentials and degrees, followers over friendships. It leads to movements like EA and AI doomerism, to the point where people change their whole life trajectory to attempt to help an infinitely large amount of potential future people because the utility from that is a bigger number (longtermism).

"it pisses me off that for about a decade in certain circles ea and its dozens of brainworms somehow monopolized “being helpful to the world”, and demonized (and continues to) so many wonderful and good hearted people who were trying to be helpful in non-ea-coded ways"

The intentions are great (sometimes the outcomes are great too), but the worldview is so all-encompassing that adherents are unable to allow, see, or even imagine other possibilities.

To delve deeper, let's define some terms:

- Image: a representation (a map pointing to the world)

- Worldbuilder: a creator of images (a mapmaker)

- Idols: false images (a map mistaken as the world)

- Idolatry: worship of false images (living as though the map is the world)

When I elevate an image to the status of an idol, I transition from using it as a mere tool to perceiving it as an entire system, from a simple map to an encompassing reality, from a signifier for what is signified. But I recognize that images themselves are neither inherently positive nor negative. Not everything escalates to a level of worship, though some ideas do (money, status) more than others. It's how I see them - where are their proper place? Where should images stand in priority?

So worldbuilding itself may not be idolatrous. Rather it may enable the conditions for idolatry by framing it's creations as reality. It opens the possibility for monopolizing frames - whether it's technologists fixed on apps, an incel consumed by a fatalistic resentment, a cult's dogmatic beliefs, or trauma victim.

If worldbuilding shapes our environment, it acts as a medium, creating new worlds for us to live in - a new Atlantis, Eden, or Babel. I don't speak as if I'm immune; it's invisible to me as to anyone else. What I'm looking to understand is to recognize it as such.

Worldbuilders, whether knowingly or not, lay the groundwork for idolatry. Thus, those those intentionally engaged in de-creation or "world destroying" are pivotal to help us discern the proper place of man's creations. They offer antidotes to the "one way" with in the negative space they open up, creating what McLuhan terms an "anti-environment."

This is the essential role of an iconoclast, a breaker of current images.

#Man's Image

Ivan Illich was one of them: a historian who questioned the certainties of modernity. My last essay was approaching him on the importance of limits, particularly in relation to public goods and language. Here I'm exploring how iconoclasts act as limits to the power of images by acting as boundaries between an image and an idol.

I'd like to share an excerpt from his critique of schooling, containing the title of this post:

..contemporary man goes further; he attempts to create the world in his image, to build a totally man-made environment, and then discovers that he can do so only on the condition of constantly remaking himself to fit it. We now must face the fact that man himself is at stake.

In Genesis 1:26-27, God creates humanity in his own image. His further exhortation for them to steward the world might explain the desire to create:

God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.”

I use the word steward, since it seems clear to me in Genesis that it is God who is creator and man who is creature (one who is created). God creates the heavens and earth, with mankind being included in all of creation.

But rather than a world where all has been given as a gift from the creator, it is (especially) contemporary man who believes he lives in a world that is entirely as Heidegger's standing reserve, an image of the world as raw materials ready to be used.

Man as Homo faber (man the maker) is man as toolmaker. As Illich argues in Tools for Conviviality, people need new tools to work with rather than tools that work for them (augmenting vs. replacing). Tools that lose the balance of what the machine does vs. what a person progressively turn the role of persons from makers into consumers in a system. Rather than active citizens, neighbors, and family, people may become so passive that they may seem or feel like tools.

God blesses man and asks for humanity to "rule" (also translated as dominion), on God's behalf as a representative. But perhaps that has been used as an excuse for exploitation, where man feels entitled to use this gift in whatever way he so chooses, while the world waits idly by to be consumed.

The totally man-made system creates a single, overarching Procrustean bed for man to be fitted into, which parallels C.S. Lewis' warning of the perils inherent in Man's conquest of Nature (without disparaging what has been good), namely that the final battle and victory becomes human nature itself.

It is not that they are bad men. They are not men at all. Stepping outside the Tao, they have stepped into the void. Nor are their subjects necessarily unhappy men. They are not men at all: they are artefacts. Man's final conquest has proved to be the abolition of Man.

T.S. Eliot's verse on creating systems so perfect is Illich's view of a totally man-made environment, Lewis' abolition of Man, the utopia of the Matrix. It's the latest hype cycles: a trustless crypto world of code as law, a H100-filled chatgpt world of Shoggoth AIs, a dis-embodied metaverse of virtual avatars. Instead of people, man creates a form of man, an android. Instead of creating artifacts, man becomes the object.

Man, though only a creation, deems himself as creator. Good intentions, sincerity, sacrifice are all used to create a bureaucracy, a brave new world, a system. The idol is not man himself but the system he intends to put in place of people.

Illich sees that these systems may fall under the weight of their infinite scope and reach such that some will be forced to likewise realize they can live on without the system. The system can be seen as an idol (powerless to save) precisely when it fails to meet expectations.

Zizek: that AI will be the death of learning & so on; to this, I say NO! My student brings me their essay, which has been written by AI, & I plug it into my grading AI, & we are free! While the 'learning' happens, our superego satisfied, we are free now to learn whatever we want

And if I take this parody of Zizek a little seriously, maybe it'll be ok even if the system succeeds in replacing, outsourcing, removing the person from "human activity". In the example above, once "school" is done by the machines, people are then free to learn on their terms. I'm not sure.

I'm really looking for a renewed awareness of who I am, the sort Illich refers to in his first work, Celebration of Awareness. An awareness of what I'm actually doing and making, and how I may want to live in light of what systems do to me and say about me. How do I see myself?

#Imposed Images

In The Human-Built World Is Not Built For Humans, L.M. Sacasas presents an anecdote from Illich about the changing attitudes of people towards themselves.

A tourist explains that although it was upsetting, it was also the person's fault for being run over by an incoming car. Sacasas finds it easy to extrapolate to a scenario where a tourist would feel the exact same way with a future self-driving car. In each case, it is the person that needs to adapt to a constantly changing technological world, rather than the other way around.

This is the same attitude that is shared by anyone pushing for a new system, world, culture: whether it's being required to understand crypto wallet seed phrases, requirements to adapt to what GPTs will replace, or feeling pressure to use social media to catch up with friends.

Now people have always had to adapt to changing environmental conditions due to technology, whether it was spiritual, political, or cultural. It's in man's nature as a toolmaker.

My questions surrounding creation are around the effects on identity and friendship.

Not necessarily what a built-world or tool does for me, but what does it say about me? What does it say about my friends? What does it say about my enemies? How does it change my self-perception and that of those around me? What does it ask of me and of others?

Is it right to impose this learning on others because of how "helpful" this technology is? I believe this is the sense that McLuhan brings up the phrase, "the medium is the message". An increasingly systematized world is one where people increasingly believe that experts determine the terms of engagement, and get to define what is the good life, namely a deficiency in consuming an institution's outputs.

The incoming changes asked by the world-builder/technologist may not be even moral ones, but simply overcoming an ignorance of new rules as a result of what others have built (ex: that one can't walk in the street anymore, since the first class citizen of the road is the car, or at least the person who happens to be in the car), rules that may seem obvious to people that have grown up with the changes or can afford to use them.

A person is at fault for not being informed or responsible enough, and others likewise feel responsible for not educating them enough to know better (leading to adult education schools, paid courses), leading to a constant state of catching up. The builders act as the new priests, showing us their way of life through new language, new behaviors, and new relationships to a system.

In the past, people may have felt the nature of contingency, the fact that life was a free gift. But now people may have the illusion of being self-made, when they have lost much of their agency due to the complexities of current systems. Self-image becomes an increasingly imposed image by others.

#Images as Mirror

Taking from Kranzberg's laws of technology, what I create isn't neutral at all. Reading "The Medium is the Message" again, I'm reminded of a quote that reflects a common view of technology (and in this case worldbuilding, or what I create)

“We are too prone to make technological instruments the scapegoats for the sins of those who wield them. The products of modern science are not in themselves good or bad; it is the way they are used that determines their value.” - General Sarnoff

This kind of view is normal for someone who can't even imagine that created things can have negative effects, consumed by a technological ethos. It's an example of seeing everything as "standing reserve", ready for people to use. It assumes that what humans make is designed to be solely used for the sake of the end user, but that stops being the case when a tool (the hammer) becomes something else entirely in the system. The hammer gives a person both responsibility and agency, the ability to use the tool in whatever way it fits, but that isn't the case with other non-convivial tools that impose constraints that might not even be felt at first.

I don't want to be simplistic or absolute on this point regarding images and systems, or to suggest that all creation is harmful or even mostly harmful, that people shouldn't create art, that any kind of system is evil, or that people should destroy all images. I don't believe humanity is doomed to continually build Towers of Babel. It's a lot more messy, in the most human way. But I want to acknowledge to myself that creation has the potential to both cause me to lose my place in "reality" and live in a dream world or actually draw out reality in me. I hope to move beyond the belief that creation is purely additive (an extension of ourselves), or not worth pursuing at all due to the subtractive or even destructive parts.

I'm finding that every act of creation reflects my inner self and acts as a mirror to my beliefs. In the same way that McLuhan's media can act as physical extensions of the body (the Internet extends the nervous system), images illuminate my perception of my body. Media thus can amputate parts of my body (Zoom replaces physical presence), just as an image can distort my perception of my body.

Coming full circle again, I'm reflecting on how McLuhan see's the artist as the one that best understands the medium. Being at the edges, the artist is the most aware of how the medium affects the body. So maybe it's ironic that any act of creation is also an act of "de-creation", because the message (content) of any medium is another medium. By presenting a contrast to the viewer, the artist is able to make something new that gives the viewer a standpoint to be able to weigh how they have seen the world. The environment only becomes visible, the viewer only aware of his/her surroundings in the presence of art. Using that famous story, the fish is able to understand water in a new way, precisely when it leaves it.

Images have great purpose, precisely in directing a viewer to what it points to. A sign that refers to it's signified. The danger is when an image becomes the signified itself like an ouroboros, or the reality disappears from under it and there is no distinction. The praise of an image becomes the worship and addiction to it, the engagement with a tool becomes a dependency. The recursive nature of idolatry may reflect its own devotion, an image pointing inwards on itself, spiraling like an abyss.

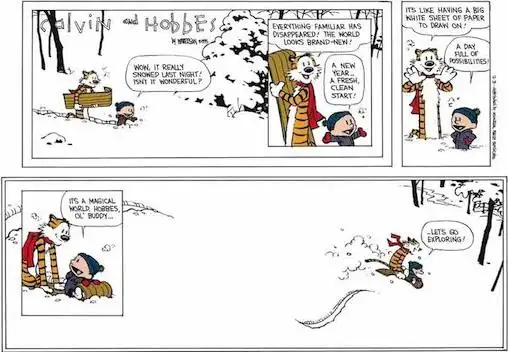

So fighting idolatry may require not an Archimedean point, but any other standpoint to better understand the current one, whether it's a new location (travel), a different time (history), or a different way of life (culture). Or going back to worldbuilding again, immersing oneself in another world (fiction).

I think the hope of iconoclasm isn't to be destructive for its own sake, but as a remedy for disordered images. It may better reveal what is actually happening (like the emperor's new clothes). The worldbuilder or artist can simultaneously be the iconoclast in a necessary process of re-evaluation. To break an idol is not to shun creation, but to reclaim it from the cliff of misrepresentation.

#Idolatry Everywhere

The core of idolatry seems to be a delicate balance of the actual function of images. As a gateway to reality, images do their job of pointing away from themselves to a greater truth, whether images are of the world or the self.

No wonder many religions called adherents to a life of self-denial. They all understand the temptation to idolatry. But negating one's self worth isn't destroying one's image, it's just replacing an egoistic image of superiority with one of inferiority. The Gospels speak of a self-forgetfulness, a shifting from self-centeredness to others, while being able to see myself as God sees me (assuming he is objective, the standard).

So it makes sense that the end of my writing is always the least edited and most personal, as it's the part I want to procrastinate. It's easier to do a lot of research, quote others, and talk about what seems factual, objective. What I can't seem to face is the pain of reliving moments, feelings, that should be addressed. There's too much to say that'll never go in..

Even writing this essay became idolatrous: what started off as a spur of the moment musing has already taken half a year to get out. There's always more to add, more points of view to consider, people and history not brought to light. The longer the writing, the more it feels like it needs to say something meaningful or profound, or I've wasted my time and my reader's time. The inertia is also such that I get tired of editing the same beginning paragraphs and never end up writing the ends. What was the whole point again? Was there one really to begin with other than an interest in the subject?

The "things" that I want are incalculable, unattainable, ineffable. The fact that I think it's a thing at all is the reality I'm creating. An abstract notion of happiness or fun. I use it like a noun I can grasp, measure, hold. so it's no wonder I want to be able to see it, or grab the closest thing I believe approximates it in physicality. So I settle for substitutes and believe it to be the "real" thing.

This is probably what each translation of Dao De Jing attempts to convey: the issues of fixating on one "way"?

- A Tao that can be tao-ed is not lasting Tao.

- The Tao described in words is not the real Tao.

- The way you can go isn’t the real way.

- The way to which mankind may hold Is not the eternal way.

Worldbuilding creates a framing that turns idolatrous when it becomes the sole or main way. Whether it's a fictional story or an industrial complex, what I create changes the scale of human affairs at levels I find hard to recognize. What's required to fight a dominant frame is a continued opening of counter narratives, which the iconoclast does by opening a way. Through the acts of proscription (to forbid) and prescription (to follow), the artist challenges prevailing views and brings forth the possibility for second thoughts.

#The Great Iconoclast

"Images of the Holy easily become holy images — sacrosanct."

In this time of Advent, what has come is yet another image: namely the full image of God in the person of Christ, who claims he is the living Word.

In Jesus Christ, there is no distance or separation between the medium and the message: it is the one case where we can say that the medium and the message are fully one and the same.

For McLuhan, the medium wasn't just the message, it was the messiah. Christ as the true light tells a message about himself through himself, in his incarnation, his coming. The Word became flesh. I've only begun to realize how great a testimony of God it was, as God places himself into history. A literal skin in the game.

What are we to make of this? Christ asks his disciples to deny themselves, take up their cross, and follow him. So as an image bearer of God, I am also called to act as a living sign to others. Better yet, a living portal. A life of fellowship in the Church is one where each person is continually entering and participating into one another's lives, ultimately participating in the life of God together. For the Church is his body. Illich calls this "extending the incarnation", that each of us may continue to act as enfleshed beings that freely show God's love to one another.

It's when I can see myself as created in the likeness of God I can better understand the differences between image and idol. C.S. Lewis so powerfully explains the pain of letting go of a false image after his wife had passed. He reflects on his understanding that he needs Christ just like he needs her, not his idea or picture of her.

My idea of God is not a divine idea. It has to be shattered time after time. He shatters it Himself. He is the great iconoclast. Could we not almost say that this shattering is one of the marks of His presence? The Incarnation is the supreme example; it leaves all previous ideas of the Messiah in ruins.

So on this Christmas day, it's fitting that I would be reminded that Christ himself can be both the ultimate image and image breaker, medium and the message. He contains the infinite within the finite, an inside bigger than it's outside. It's then that I may be better able to steward the gift that is the world in his image, rather than mine. After all, I'm not my own.